Daniel Bashir

distributed compilation and remote execution

Motivations

Compile times, especially for large projects, can be very long. Most of us don’t worry about this too much, but it’s a big deal for things like high energy physics experiments, where, according to this paper by Rosen Matev, compiling from scratch can easily take 5+ hours even when using an 8-core VM. Incremental builds don’t help much if you change something like a widely-used header file.

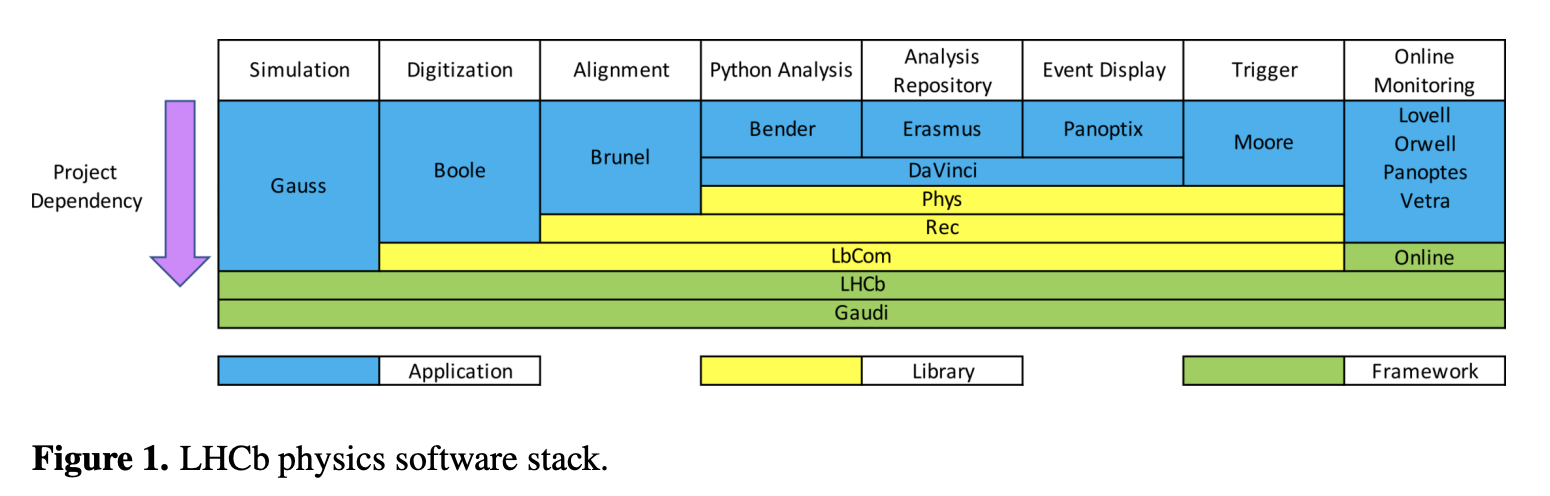

As Matev explains, high energy physics experiments typically have large software codebases written in C++. The LHCb physics software stack is fairly complex, and is depicted below:

LHCb physics software stack

Here’s how Matev explains the difficulties:

Developing on such a codebase can prove difficult due to the amount of resources required for building. Typically, development happens on hosts that are readily available but often not very powerful, such as LXPLUS, 4-core CERN OpenStack virtual machines (VMs), desktop PCs. After building once, incremental builds are supported, but often the increments are very large due to modifications in headers or when switching branches. To combat the limited resources, custom tools exist for working on partial checkouts on top of released project versions [2], however they are not well suited for other than trivial changes due to, for instance, the lack of good support for standard git workflows, or the need to checkout a large chunk of the stack.

distcc

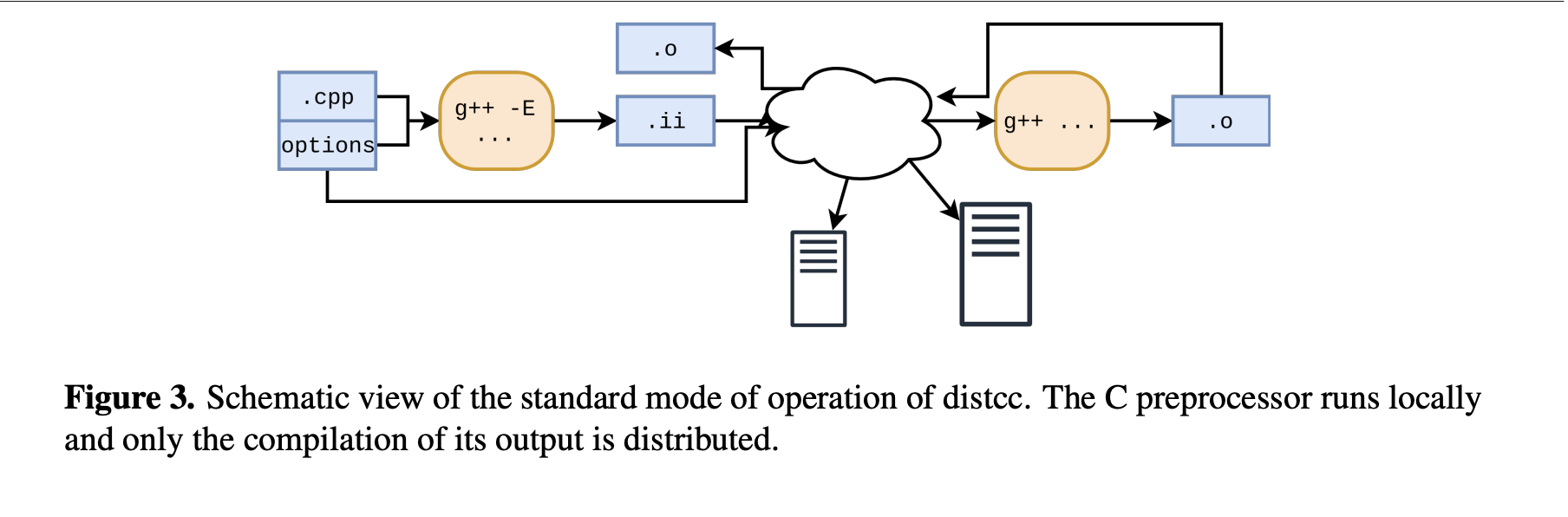

In this paper Matev describes the distributed compilation server distc. The schematic below illustrates how it works at a high level — distcc allows offloading compilation to voluntary or dedicated resources. This isn’t really a compiler — it’s a system that lets a client offload compilation to available resources. I’ll describe the design below, but it’s work noting that this is living in CMake world. If you’ve heard of Bazel, its remote execution feature can achieve similar results.

distcc Schematic

It works in two modes:

- Standard Mode: A client runs the C++ preprocessor locally, and preprocessed output is sent to the server for compilation. This mode is limited by local preprocessing speed.

- Pump Mode: This uses an “include server” on the client, which analyzes source files to find header dependencies. Source files and necessary headers are sent to the server, then preprocessing and compilation happen on the server. This mode asumes system headers are identical on the server and client.

There are a few other important components:

- Servers use GSSAPI authentication and clients authenticate using Kerberos tokens.

- distcc uses the Ninja build system with 100 parallel jobs; “pools” limit concurrenty for non-distirbutable tasks like linking.

- Uses the CernVM File System to share LCG releases (CERN lingo: a set of ~200 software packages consistently built together).

distcc’s Distributed Cache

Sharing caches is hard — developers might use different directories and info contained in lookup keys might contain absolute paths, e.g. when including debug symbols. sccache natively supports remote storage such as S3 or Redis — like ccache, it’s used as a compiled wrapper but has a client-server architecture for efficient communication with the remote storage. Its lookup key determination is also more simple than ccache — this means fewer cache hits, offloading the cache but not sharing it between developers.

Bazel and remote execution

Bazel’s remote execution achieves something like that DistCC was built to do: you can distribute build and test actions across multiple machines, e.g. in a datacenter. Bazel goes beyond DistCC in its ability to scale entire build processes (including non-compilation tasks).

Misc

There was what looks like a Stanford class project from 2014 called “sdcc: Simplf Distributed Compilation” — its goal was to be language-agnostic, unlike distcc, and work without meta information.

Google has a patent on Distributed JIT compilation. I haven’t read the whole thing yet, but at a high level it sounds like what you’d expect: a client platform sends a first request message to a dedicated compilation server, compiling the bytecode sent in that first message into something the client can execute, notifying the client, then sending a second message from the client to the server requesting the instructions and accessing the repository to move the instructions from the server to the client platform.

Icecream describes itself as a distributed compiler with a central scheduler to share build load. Again, not an actual compiler: it takes compile jobs from a build and distributes them to remote machines. It’s based on distcc but uses a central server to dynamically schedule compile jobs to the fastest free server.

Google’s distributed compiler service for open-source projects like Chromium and Androis. It’s basically distcc+ccache.

Jussi Pakkanen has a few notes on architecture for a distributed compilation cluster here.